The Treaty of Portsmouth

Queen Anne’s War (1703-12) between England and France came to America in the form of European attempts to secure Wabanaki allegiance and the territory they controlled. Wabanaki-French raids terrorized the English, pushing them from their Maine settlements back towards Portsmouth. English attacks disrupted the First Nations’ livelihood.

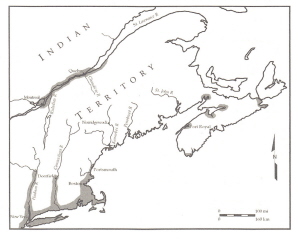

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ending Queen Anne’s War in Europe attempted to set the French and English boundaries in the New World. It put the English in charge of coastal Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine and gave France control of the St. Lawrence River valley around Quebec. The land in between was Wabanaki territory and both France and England agreed to respect the other’s First Nations allies. The Wabanaki questioned how France and England could be talking about control of their ancestral land. For there to be peace in the dawnland, a treaty between the English and the Wabanaki was necessary. The meeting in Portsmouth, July 11-14, 1713 was important for the First Nations diplomacy employed, the acknowledgement of a New Hampshire governing Council separate from Massachusetts and for the impact it had on opening the Portsmouth door to development as the commercial and military hub on the frontier. The issues discussed in Portsmouth in 1713 have a direct connection with ideas concerning the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People today.

ENGLISH AND FRENCH ENCOUNTERS

The English and the French both sought the First Nations as allies and trading partners in the hostile wilderness. The French had limited territorial desires beyond establishing forts manned by small military garrisons to protect France's fishing and fur trading interests. As a Catholic nation, the French outposts soon acquired Jesuit missionaries, who also lived with the native tribes and tried to connect with their cultures to convert them to Catholicism. In contrast, the English were committed to settlement and territorial expansion in North America and were vigorously and politically opposed to the "Papist Catholics."

The English settlers were suspicious of their native allies and often considered the native peoples to be "savages." The English built large forts, cleared land that the Wabanaki had claimed as traditional hunting and fishing grounds, and were slow to implement the tenets of agreements they made with the Wabanaki diplomats who sought compromise. But at this time the English had only a few – diminishing – toeholds along the coast and rivers (shaded areas in the map, above), and the success of their expansion was in no way guaranteed.

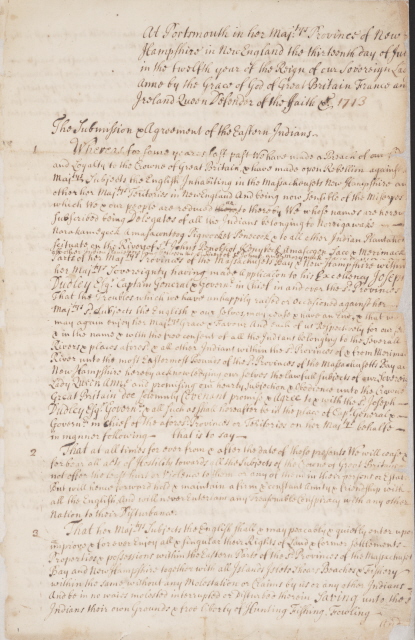

The meeting in Portsmouth in July 1713 was not the first between Governor Dudley and representatives of the First Nations. Five previous treaties had attempted to agree on trade issues and on the extent of forts and settlements in Wabanaki territory that the English had claimed before being driven out by the wars. Both sides understood the need to end the warfare. The Wabanaki wanted three things: 1) the limitation of English expansion so that the Nations could preserve their culture on the seasonal hunting, fishing and planting grounds; 2) trustworthy trade partners in more convenient trading locations; and 3) diplomatic protocols including the exchange of gifts. Governor Dudley’s speeches that were translated to the Wabanaki asked permission for the English to return only as far as their earlier forts and settlements and promised fair trade. Dudley needed proof to show the Queen and his own settlers that England was in control of the disputed land and that the Wabanaki would no longer ally with the French. The written treaty contained language of Wabanaki submission to the English Crown.

During his time as Royal Governor, 1702-1715, Dudley tried to find accommodation, meeting with the Wabanaki on their home ground at Casco (where he added tribute stones to the memorial cairns placed in 1701 at the conclusion of a diplomatic mission to the Wabanaki by English commissioners), responding to their trade requests and asking permission for the English to return to their previous forts and settlements in his face to face meetings that were the basis of First Nations diplomacy. This approach contrasted with the language of submission he was required to secure for the Crown.

The Wabanaki understood the spoken word of the English differently than the written words of submission. The Wabanaki granted the English the permission they sought to return to their former forts and settlements and did not consider this submission. Both sides accepted the written Treaty as a symbol of friendship. After 1713, peace brought prosperity to Portsmouth because Dudley practiced the diplomacy that was the pragmatic answer for the Crown, for the colonies and for the Wabanaki.

This website and planned exhibits, programs and other commemorations were created by the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth Tri-Centennial Committee for the 300th anniversary of the signing of the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth, Charles B. Doleac, Chair.

Calendar of Events

What started as conversations with First Nations descendants of the tribal groups who participated in the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth meetings, quickly became a dialogue on the history of First Nations contact with Europeans and other non-native people and the impact of that history today. Continued research opens new conversations with native scholars, museums engaged in decolonization initiatives and others interested in how the aspirational goals of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples are being realized.

Comments on this site and 300th Anniversary:

"Thank you greatly for the documents re Treaty 0f 1713. They arrived just in time for me to start research and preparation to serve as expert witness in a court case. The lawyers I have been working with were thrilled to see such beautiful copies. In fact they asked to give your copy of the Treaty itself to the judge... I also looked at your wonderful website and appreciate that at least one treaty with Wabanaki peoples could be so celebrated."

-- Andrea Bear Nichols, retired Chair in Native Studies, St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick

"From the beginning Treaty was the way of doing business on Indian terms. They are authoritative documents, legal documents. These treaties are foundational documents for the US. ...But a treaty is just the end product, the written end

product of a conversation intended to establish a relationship between the English (etc) and the Indians. .. The 370 treaties that already existed are covered by Article 6 of the Constitution. They remain the law of the land. They still

apply. They still matter.... The Indian people understand what was done. Their issue is not with the details of the treaties but with how they were used, broken and ignored. The sense I get from my Native American colleagues is that they want

to re-establish the human-to-human relationships they were trying to establish 500 years ago – to recognize the best practices the US as a constitutional democracy should employ in relation to the 500+ tribal nations still here. They want Treaty to be the basis for future understanding in the 21st century." -- Colin Calloway, Native American Studies and History, Dartmouth College, on 300th Anniversary, July 14, 2013.